The first women’s suffrage movement in 1848, beginning with the Seneca Falls Convention, did not involve Black women. Black women were rejected from participating. Suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony infamously said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” Black women were considered Black before they were considered women; the Black women’s experience of feminism is entwined with her experiences of racism and classism.

When one thinks of leaders in the suffrage movement, they immediately think of white leaders such as Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Frances Ellen Harper, Mary Ann Cary, and Sojourner Truth are an afterthought if known at all. However, Black women played an integral role in the women’s feminist movement. In the late 1800s, they attended political conventions to plan strategies, worked for churches and newspapers to gain a platform, and some, including Mary Ann Cary, testified before the House Judiciary Committee about the importance of the right to vote. However, white suffrage leaders downplayed their work. The National American Woman Suffrage Association prevented Black women from attending their conventions, and Black women had to march separately from white women in protests. As Treva Lindsey stated, “the problem we [women of color] endure is one of constant erasure.”

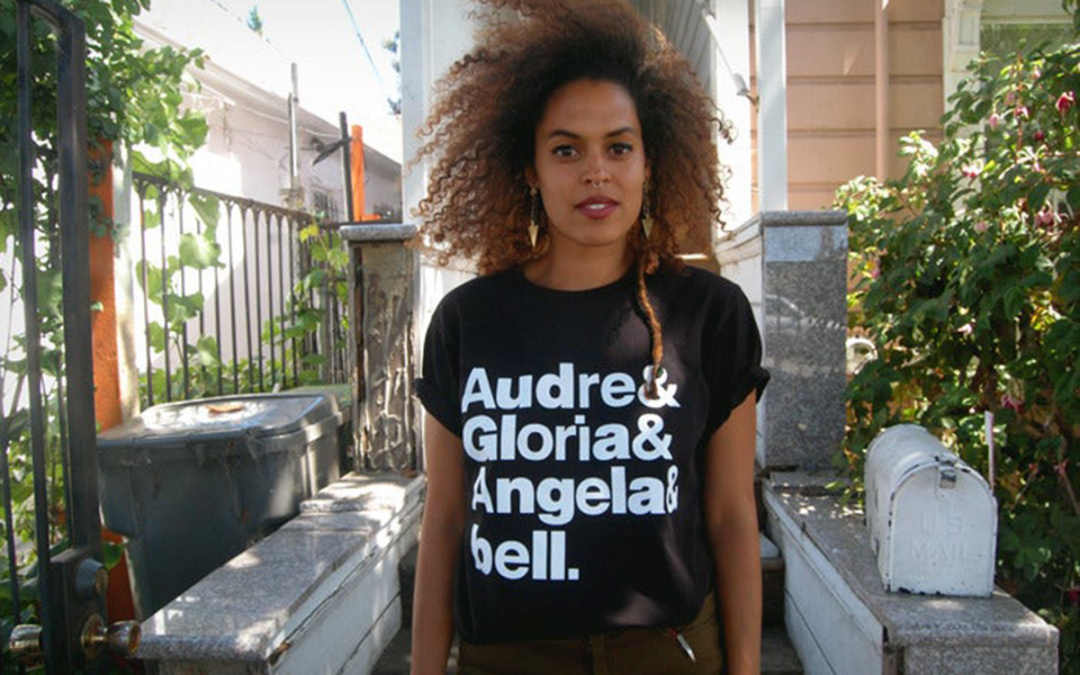

Black feminism hopes to combat this history of erasure and bring issues of direct concern to Black women to the forefront. Modern thinkers behind Black feminism, such as bell hooks, Angela Davis, and Audre Lorde challenge feminists to consider gender’s relation to race, class, and sex. This focus on intersectionality brings attention to all the ways in which past feminist achievements were gained through racist tactics, and also advocates for a united front in which all individuals, regardless of race, class, and sex, may come together to fight for equality. In her book, Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery, bell hooks stated, “no level of individual self-actualization alone can sustain the marginalized and oppressed. We must be linked to collective struggle, to communities of resistance that move us outward, into the world.”

Richa Parikh is a Courageous Conversation Global Foundation Intern and part of the Schuler Scholars Program. She is a first-year student at Claremont McKenna College majoring in philosophy and public affairs.